Because KIT respects the wishes of its researchers, it made me feel more strongly about using plasma technology for the benefit of society.

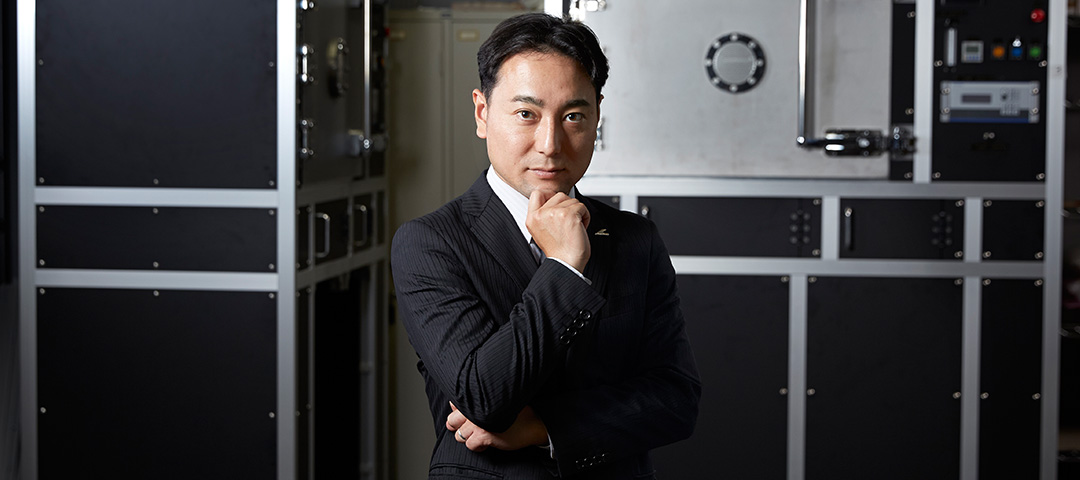

In 2002, when you were still in the Doctoral Program at Kyoto Institute of Technology, you established the university-based startup, SAKIGAKE-Semiconductor Co., Ltd., which is known for its innovative plasma equipment. I understand you actually enrolled with the aim of setting up a company, but why did you decide on KIT?

Taguchi: Before I enrolled in KIT’s graduate school, I was working at a semi-conductor manufacturer in the Kansai region. My supervisor there recommended a number of universities to me, one of which was Kyoto Institute of Technology. What drew me to KIT in particular, was the close lecturer-student relationships, and the atmosphere of warmth at the university. Having conducted plasma research in my undergraduate days at another university, I had spoken to KIT lecturers at academic conferences, and gained the impression that it was a flexible and supportive university. My time at KIT only confirmed that impression. I also found interdepartmental collaboration at KIT highly beneficial. Research programs there are advanced without the constraints of specific fields. This creates a fertile environment for diverse ideas making it an ideal place for researchers.

You had a promising position where you were employed, what motivated you to set up your own business?

Taguchi: At the time I was employed, the public had become aware of the poor treatment of engineers. Dr. Shuji Nakamura, the professor of engineering who received the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physics for inventing the blue LED, had successfully sued his former employer for inadequate compensation. That’s just one famous example, but there was a time when, even though Japan was hailed as a technology-oriented nation, the people who employed the engineers were given more preferential treatment than the engineers themselves. At work in the company, I saw the difficulty engineers had in staying motivated, for myself, and it led me to wonder if I could create an environment where people who worked hard would be recognized for their efforts. Could I start a company where engineers would be motivated and feel appreciated?

So you quit the company and enrolled in the KIT doctoral program. That was quite a unique career move, wasn’t it?

Taguchi: At the time I completed my masters’ degree, working at an established company was the only career option available. No sooner had I joined a firm, however, than the startup boom began and the climate for business ventures in Japan became more proactive. So, instead of diving deeper into that established company, I decided to set up a company where engineers would be legitimately valued. I enrolled in the doctoral program to come up with the impetus for it. I had been conducting research into thin-film formation using plasma since my undergraduate days, and I knew that it had a wide range of applications, so I wanted to use that technology to benefit society.

What kind of phenomenon is plasma, exactly?

Taguchi: Electrons exist around the periphery of molecules, and, in simple terms, a “plasma state” is when these electrons move away from the molecules (ionize), and become unstable. Having lost electrons and entered a plasma state, the molecules try to stabilize by stealing electrons from or sharing electrons with nearby atoms and molecules. In other words, it becomes easier for chemical reactions to take place. I wanted to apply plasma technology, which causes chemical reactions that normally would not occur, to unexplored fields, such as the world of biotechnology.

How was your desire to create a startup received at the university?

Taguchi: When I told my supervising professor, “This is what I want to do,” he said, “Feel free to give it a try.” He respected his students’ ideas. Thanks to his supportive attitude, I was able to forge ahead with research and development that was consistent with my interests. With my strong sense of independence, the environment in that laboratory really suited me. On the other hand, when it came to actually setting up the company, I received extensive back-up from professors. They even assisted me with securing R&D funding. Thanks to this support, in 2002, my second year in the doctoral program, I launched SAKIGAKE-Semiconductor, with myself, at 28 years of age, as its sole employee.

So you started with just yourself. What kinds of struggles did you come up against after you started the company?

Taguchi: I wouldn’t describe it as a struggle exactly, but after about three or four years, I came up against the gap between my preconceived notions about startups and the assumptions held by those around me. My image of a startup was not of a company that staked everything on a innovative dream technology or idea, but of one that would generate enough profit to put food on its employees’ tables. Running a company on the wheels of both innovative dreams and livelihood is the traditional management style of manufacturing companies in Japan. Panasonic, and here in Kyoto, HORIBA Ltd., fit this description. These companies keep employee livelihood in mind. That is at the foundation of their research and development plans. I was aiming for something similar, but I had trouble conveying that to the people around me. In fact, when I first set up the company, I dreamed of a lot of ideas that I was convinced there would be a need for and started developing them, but none were very successful. The business only stabilized when I began listening to what my customers said they needed and started to create products in response to those needs.

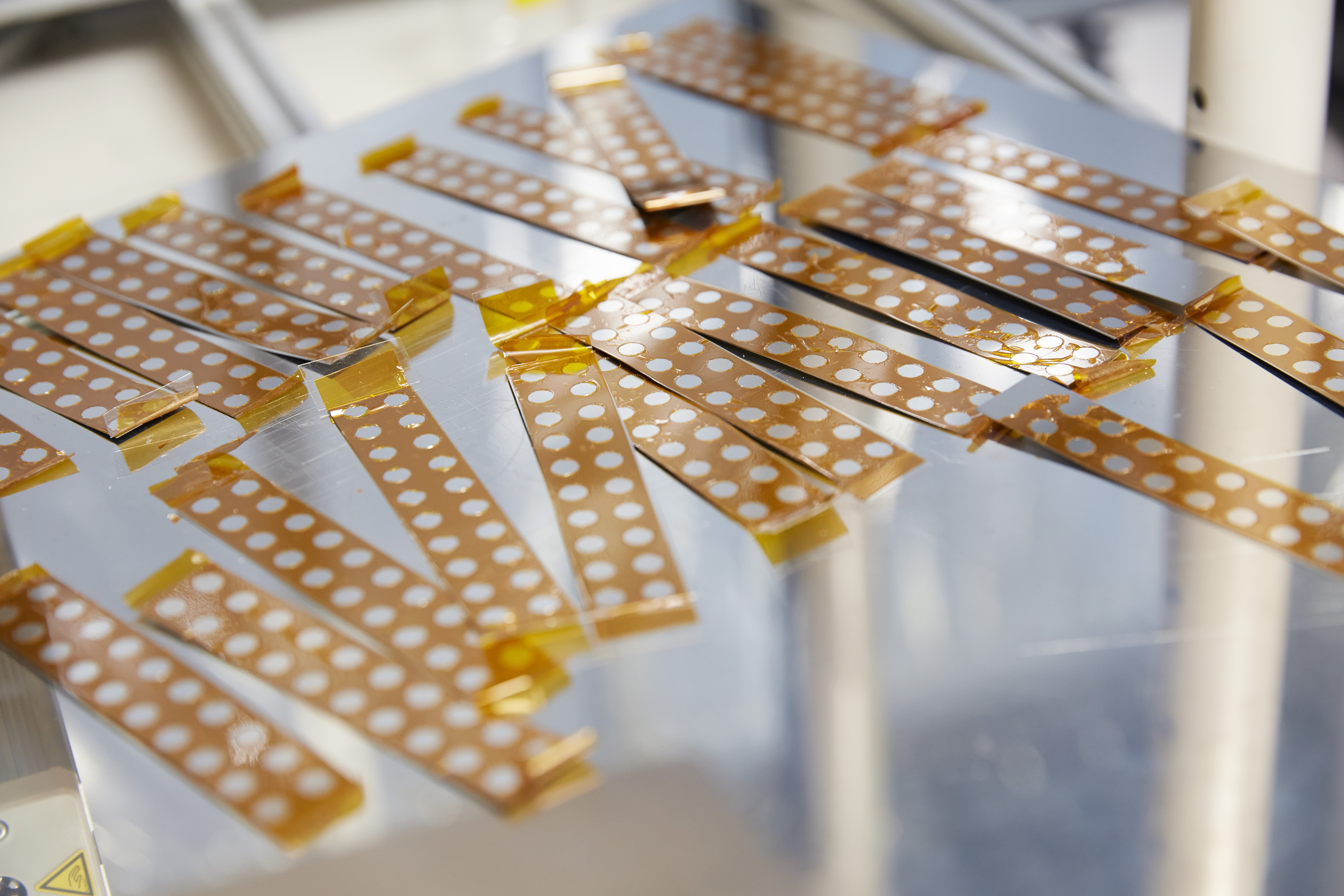

The turning point came with the first proprietary product you launched in 2006. Wasn’t it desktop vacuum plasma equipment?

Taguchi: That’s right. At the time, plasma technology was used mainly in the manufacture of semi-conductors and displays, but the equipment needed for it was enormous and seriously expensive. I set my sights on a solution to this problem and launched the desktop vacuum plasma equipment. Equipment that used to cost more than ¥10 million could now be purchased for less than a million yen. It continues to sell well today. The launch of this equipment prompted inquiries from fields that had been unaware they could use plasma technology, such as biotechnology and medicine.

What prompted you to sell such a specialized piece of equipment at such a low price?

Taguchi: Plasma technology can be applied to automobile and food product technologies and a variety of fields outside biotechnology and medicine. The reason no popularly priced device was on the market before ours, was because of the number of functions available on conventional plasma processing equipment. My R&D focused on bringing the price down by limiting the number of functions. In other words, by deliberately narrowing the number of functions, I intended to extend the potential applications for plasma technology to fields where simpler equipment would get the job done.

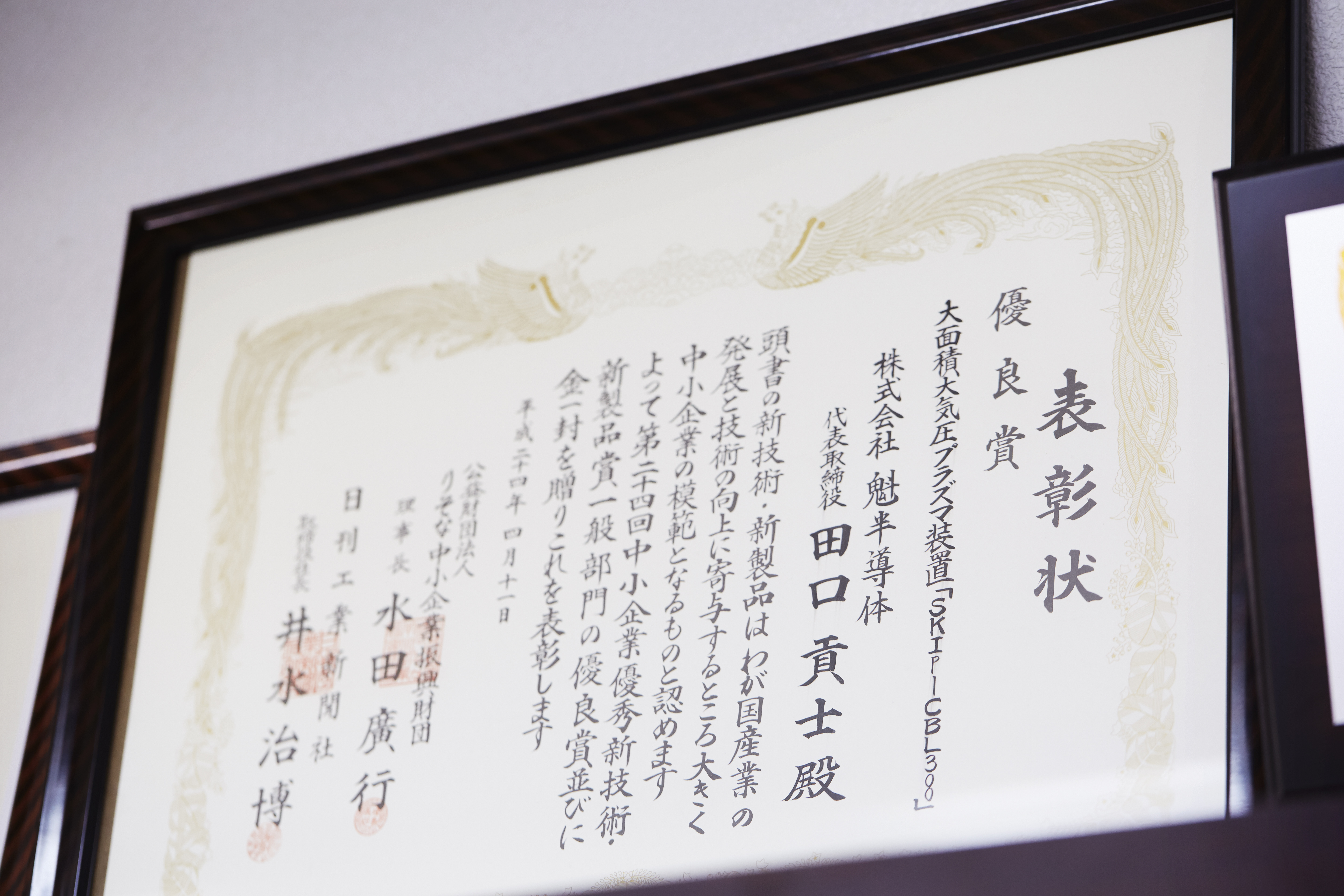

Limiting the functions of a piece of equipment to widen the extent of its application is an interesting concept. The atmospheric-pressure plasma processor you launched in 2010 won the Kyoto Prefecture SME Technological Excellence Award. What prompted you to develop it?

Taguchi: It was prompted by a request our company received in our second year of business. A major automobile manufacturer wanted us to develop a device for plasma processing carbon powders. We weren’t able to achieve this at the time, but a corner of my mind was always working on how this could be done. Then, five years later, when I was researching another product on my own initiative, I happened to think of a way to solve this problem. Partly because it was a world-first, when I turned it into a commercial product, it was exceptionally well received.

What are the applications or areas this equipment could be used in?

Taguchi: Most recently, it has been used in the manufacture of electrode agents for lithium-ion batteries. Using this plasma processor makes it possible to cut back on the intermediate agents needed in the process of making electrodes. In recent years, expectations for the use of electricity to move things, such as drones and electric vehicles have been on the rise. We are also seeing more everyday products that use batteries, such as smart phones, and wearable devices that look like watches or glasses. It seems the demand for these kinds of products is likely to increase in the future, and the potential of this equipment will expand accordingly.

So this equipment has a bright future?

Taguchi: These days, we hold regular product exhibitions, where we canvas visitor opinions. In fact, it was a customer who told me about the need for an atmospheric powder plasma processor. Even though we didn’t succeed at first, by continually attempting to respond to our customer’s request, we were able to open up a path to eventual success. This is something that I try to adhere to in everything I do, from manufacture to business management. That is to say, whenever I come up against a failure, a suspicion or a problem, I think of improvements and try them out. There is only a finite return on routine work. People who think of improvements and expand their potential have a lot more to gain. This has been my conviction since back when I was doing my masters’ degree and it still is.

Students who have a wide range of interests have far more potential than researchers who limit their thinking to the commonly accepted wisdom of their specialty.

What were some of the benefits of forming a university-based startup?

Taguchi: For the first several years after the company’s launch, I ran it from the university, so if I had any problems, there was always someone nearby I could ask for advice. Of course, I’m talking about professors, but at that time, with the incorporation of the national universities, the universities themselves were starting to change their way of thinking, and to realize that they needed to make better use of their intellectual property and become more profitable. Having many channels close by that I could rely on when something happened gave me great peace of mind.

Will you be conducting any joint initiatives with the university in the future?

Taguchi: Universities have an advantage over companies in that their specializations can elucidate fundamental phenomena. Taking part in that kind of research makes the job of development more efficient, and I am also able to ensure better protection of intellectual property. In that respect, working closely with universities on research can provide the advantages that enable companies to push their business forward. In my field, plasma technology came first, and the basic research followed. Still, there are times when the outcomes of that basic research are put to use in products. Again, I think it is important to have both these wheels (research and protection) when pursuing development, which is why I want to continue to actively forge associations with the university in the future.

You also teach at Kyoto Institute of Technology. What is your impression of the young researchers there?

Taguchi: I get the impression that more of them have a broader range of research interests than before. In my day, most people didn’t look at other areas. Instead, they completely immersed themselves in their specialties. Recent researchers, however, have much better presentation and communication skills, and quite freely interact with people in other specialties. They are able to talk about their ideas for innovation – that’s the impression I get, anyway. Another thing I like about interacting with students is that they suggest things well beyond our conventional wisdom. It is often said that “experience impedes innovation.” In fact, the more you learn about something, the more difficult it can become to talk about your ideas for new directions or products. Some of the comments made by students, who ironically benefit from a lack of experience, are full of potential new directions for companies.

Tell us about the future goals for your company.

Taguchi: One goal is to release a plasma-technology-based product targeting the general consumer sometime in the next five to ten years. I will make this technology widely available and make it familiar to more people outside companies and research labs. Meanwhile, in terms of the company’s direction, I still treasure the intention I had when I started the company, that is, to “create a place where people who want to work hard, can.” Employees who passionately wish to pursue new directions can take that challenge as far as the company’s business situation allows. That is the kind of company I want ours to be.

Have you made any concrete moves towards that goal?

Taguchi: I have an employee pushing to market our products overseas, so I have said that they can try and sell whatever products they like, starting with the plasma products. We have already sold our products overseas, but this has not been through any proactive efforts on our own part; it just happened. It is only recently that we have started to make proactive moves to market our products overseas. To make Japan’s plasma technology available around the world, we plan to actively handle the products of other companies, as well.

It’s exciting to imagine Japanese plasma technology spreading to the rest of the world, isn’t it?

Taguchi: I believe that Japan’s greatest strength still lies in “making things.” Overseas production has become more prevalent in recent years with the establishment of low-cost production facilities abroad, but once robotics technology takes off, the geographical cost differential between Japan and overseas is expected to eventually disappear. It is important to continue to slowly and steadily manufacture products domestically in preparation for that day. Motivated and enabled by the warm support I received at Kyoto Institute of Technology, I established my company. I now intend to continue making useful technology available globally. The creations of SAKIGAKE-Semiconductor Co., Ltd. will service to improve the lives of people the world over.