Studying in an interdisciplinary program, I started to wonder if I could change the world through its offices.

As a researcher of office spaces and working styles, Mr. Yamashita works as an office design consultant, and is the Chief Editor of WORKSIGHT, a multi-media platform that showcases various companies’ working styles. We asked him why he chose to enroll at Kyoto Institute of Technology.

Yamashita: I grew up in Kyoto and when I was in junior high school I thought I would probably go to Kyoto Institute of Technology. Can you believe it?! I had a fairly broad range of interests, and I couldn’t decide whether to go down the humanities route or the sciences route. I wanted to study a mixture of disciplines and take time to decide what I wanted to specialize in, so I was drawn to universities that offered a fusion of the sciences and humanities. The department I enrolled in was Design Engineering and Management, which had only just started. It had the three pillars of those disciplines in a single department and aimed to solve the problems of society from multiple perspectives. The new concept this department presented was a very good match with my interests.

When did you first develop an interest in space and design?

Yamashita: It was around senior high school. I wasn’t completely sure, but I did have an attraction to places that were on the front line of ”making things.” In particular, when I saw an architect on television, I remember feeling, “Some people have interesting jobs.” I was intrigued with the idea that space use could control people’s behavior and feelings. With architecture, much of the attention is on the design aesthetic, but from an early stage, I had a strong interest in how people behaved in those spaces.

You couldn’t just sit back idly in class and just listen to lectures either, could you? (Laughter) I understand you specialized in researching offices from your third year of undergraduate studies through to graduate school. Why was that?

Yamashita: The types of buildings we study in the architecture textbooks are great edifices like art galleries and museums. But our towns don’t feature that many great edifices (laughter); they’re mostly made up of houses and offices. I also had an interest in the business side of things. So I had this vague notion that, just maybe, I could change the world just by changing its offices. One other thing, which also has something to do with why I chose KIT is that offices and their design involve a mixture of disciplines. To create an office, you need to learn about a variety of elements, from economics to organizational theory, IT trends and, of course, design. Officies undergo a great deal of change as times change. I found that complexity fascinating.

What does the study of offices entail, exactly?

Yamashita: I studied the history of the layout and design of offices, but the most interesting thing, and what I found most meaningful, was the commissioned research I undertook for regular companies. The companies would ask how they should change their offices, and the students would come up with solutions. The Design Engineering and Management department has many lecturers from the business sector, so this research with companies was very practical and beneficial.

So the school culture emphasized hands-on work over theory?

Yamashita: Another thing that left quite an impression on me was an assignment called “spaghetti cantilever.” We had to use dry spaghetti noodles to build a cantilever, using only tape to join the spaghetti together. The team that got their cantilever to project the furthest from the side of the desk was the winner. What was interesting was that the people who read the textbooks and studied hard weren’t able to achieve very long cantilevers. Those who approached it from a theoretical angle would break the spaghetti to form a triangle to make the bridge, in a “truss construction,” but it didn’t go well. Instead, the teams that would just start making it and, through trial and error, extract a solution from what was actually happening, did much better. Many of our classes followed this pattern of not trying to force the theory to fit the reality, but of using hands-on exploration to find solutions. It was around that time that Internet-based technology, such as social media and smart phones, were starting to become popular, so there was a lot of social change. I am glad that I was able to learn through this method of hands-on exploration of making things and finding solutions.

I want to use media to give people the feeling that I experienced as a student, that “workplaces can be fun.”

You joined the stationery company, Kokuyo, in 2007. What prompted that?

Yamashita: One reason was that I had been reading ECIFFO, an office design magazine that Kokuyo published until 2009, ever since I was a student. This was the predecessor of WORKSIGHT, and it was the magazine that inspired my attraction to offices. It made me realize how fun and full of possibilities offices could be. Most normal university students, when they leave university and go out into society, tend to think that they will have to suppress their individuality and become a cog in the wheel of the company. However, that magazine presented a completely different picture. It showed people working animatedly in very unique places. Incidentally, the Chief Editor of ECIFFO, Mr. Akihiro Kishimoto, is also a graduate of Kyoto Institute of Technology.

So ECIFFO was your connection to Kokuyo. Now you’re working on WORKSIGHT, which has inherited the intent of that magazine. What was its launch concept?

Yamashita: ECIFFO tended to focus more on design, so it had many fans among designers and other professionals. However, we felt that there was a need for media that gave more attention to intangible aspects, working styles and behavior. For example, recently, we are seeing the emergence of a diverse range of working styles, such as “activity-based work,” which is a combination of “remote work” and “free address” workplaces, in which people working in offices do not have assigned desks. We wanted to make WORKSIGHT a media that would present not only the design aspects, but also examples of these kinds of interesting working styles.

What are the biggest problems facing offices in Japan today?

Yamashita: I think that there is too strong a perception that workplaces have to be a certain way, that they can’t be light-hearted or flexible places. Originally, after the industrial revolution, offices were places for the clerical processing of products made in the factories. They were no more than ancillary facilities, and the real source of value creation was the factory. In those days, the most efficient offices were of an information processing style, in which documents would flow in a straight line to the boss sitting by the window. These days, however, ideas and concepts that are conceived inside offices have become important. Despite this, many of Japan’s offices are still based on those old factory-style customs.

It’s become the status quo for “the way things are done.”

Yamashita: One of WORKSIGHT’s roles is to remove the barriers of those entrenched notions. Japanese have a tendency to work for the same company for a long time, so most people don’t know what other companies’ working styles are like. We want WORKSIGHT to give these people a chance to broaden their horizons. Overseas, where people have more mobile working styles, office design is seen as an “investment” to secure the best people, but in Japan, many people think of it as a “cost.” However, we are starting to see more companies, particularly start-ups, linking the working environment with the quality of the work performed.

What are some examples that symbolize those kinds of modern working styles?

Yamashita: A lot of the examples we research are overseas, but I was involved with looking at the head office of Dwango Co., Ltd. Dwango originally experienced rapid growth on the back of ringtone services, but nowadays, it provides new creative platforms like Nico Nico Douga (the popular Japanese answer to YouTube). They consulted me at a time they were looking to create pillars for further growth. First, they wanted to bring the scattered companies in their group to one location. This style of bringing workplaces together and increasing the sense of accessibility among employees is a conspicuous trend among creative companies overseas, such as Facebook’s head office. In Japan, however, when you bring workplaces together, there is a tendency for people to form one big group, and Dwango was worried about that. We put our heads together to think about how we could make the most of people’s ideas and individuality without creating the pressure to conform to a group, and we came up with a plan to create a separate floor and different design philosophy for each department and link them with internal staircases to create a sense of unity.

So, you ensured each department’s respective individuality while also encouraging connections and interaction?

Yamashita: For example, on the sales floor, where the employees associate with various people and connect those associations to their work, we did away with assigned desks, and employed the “free address” style. We also made a point of creating complex traffic routes around the office, so people’s line of sight would move around naturally, making it easier to notice changes in their colleagues. This space then provides opportunities for communication. Meanwhile, on the floors for engineers, where people are required to express their individuality, each desk is surrounded by a partition, so people can build their “own castle.” From chairs to fixtures and supplies, each desk is customized to the individual’s taste. Some people decorate their cubicles with figurines or cosplay costumes, whatever they are interested in. In other words, these “castles” have become the source of inspiration and ideas. These floors are linked with atrium staircases. On a separate floor, a café and other places are available for employees to gather and interact.

That office won the Nikkei New Office Award, which is given to excellent office designs. The people working there certainly look very animated.

Yamashita: From the perspective of facility management, it would certainly be easier if everything were uniform, but the more uniform the space, the more tense it makes people. To avoid stifling worker inspiration and motivation, we deliberately made it into a space in which a variety of philosophies are all jumbled in together. These kinds of physical innovations in office spaces will, I believe, lead to innovation in the company. Instead of trying to fit into the company mold, I want it to occur to people to take initiative to change the existing rules themselves.

Instead of trying to fit into the company mold, I want it to occur to people to take initiative to change the existing rules themselves.

You mentioned that you have been dealing with companies since you were a student. If, going forward, you were to do something in conjunction with a university, what would you like to do?

Yamashita: I think that the good thing about universities is their open-ness to society. Companies can’t help bringing business awareness to the fore, and it’s difficult for them to make contact with people that don’t have anything to do with that business. Universities, on the other hand, can decide on which interesting challenges to explore from the perspective of “research” and become a contact point for various companies and individuals to come together to work on that challenge. If universities take this role, I think it will lead to significant developments. This is mutually beneficial. We can acquire fresh knowledge and personal networks that we would not ordinarily encounter, and the companies can tell us about technologies and know-how they have gained in the field and perhaps even provide financial support.

You have lectured at the university on topics such as working styles and offices of the future. What were your impressions of the students?

Yamashita: I think they were divided into polar opposites, between those whose individuality really stands out and those who are very quiet and earnest. There have been many advances made in the digital learning environment in recent times, and there are avenues other than university that anyone who is serious enough can take advantage of to study as much as they want. Some students with particularly good research skills are almost semi-professionals. On the other hand, I hear from various lecturers that there are many students who tend to conform to conventional molds. Apparently, at new-employee orientations a growing number of people are asking questions about company rules. My feeling is that, rather than conforming to existing rules, I wish it would occur to them to change the rules themselves.

That is exactly what your work is all about, isn’t it? From what you have said, my impression is that your work involves not only responding to the market, but actually creating new needs.

Yamashita: One of my university professors once told me to “Always have one foot poking into another area.” This is something I am constantly mindful of. At first, I didn’t really understand what it meant, but when I entered the workforce, it became clear. In these times, there is no single set of absolute values, and it has become difficult to get by with specialist knowledge in only one area. I think it’s important not to become too hung up on the rules and reasoning of a single place, but to be more “omnivorous” in coming up against a variety of things, and, in doing so, developing the “habit of thinking” to discover answers on your own. In fact, we are in an age where people and ideas that are appealing gravitate toward people who are able to think flexibly about the essence of things. What I learned at university was precisely this “habit of thinking” that I gained from coming into contact with the real world. Kyoto Institute of Technology offers opportunities to interact closely with people from a variety of fields, including businesspeople, so I think it is a good university to cultivate that habit in.

Finally, could you tell us what your future goals are?

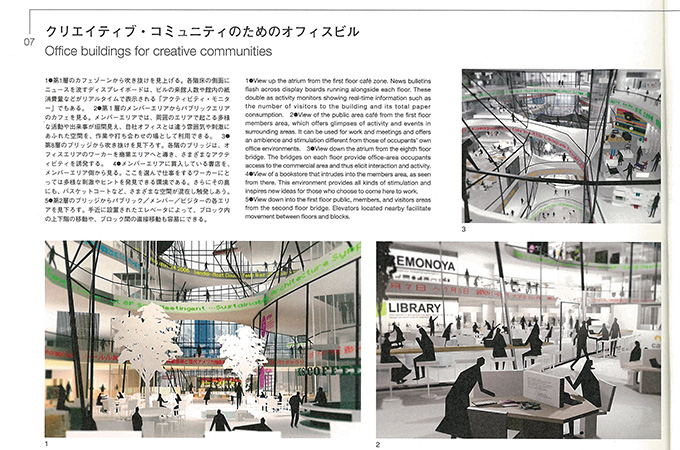

Yamashita: What I am interested in at the moment is how to raise the competitiveness of companies, not just with offices, but also through urban design. Currently, we are in an age of “inter-city competition,” that is creating attractive cities, which will lure and secure capable people and which will, in turn, impact the competitiveness of companies. I am starting to feel limited by what I can do within the confines of individual offices or buildings. Therefore, I want to broaden my horizons and give more thought to what sort of offices we should be building, and how we should design the environment surrounding those offices, from the perspective of the competitive city.

The Tokyo Olympics in 2020 are likely to have a major impact on urban development, aren’t they?

Yamashita: If I take a bird’s-eye view of my own life, I think that the period after the Olympics will be a make-or-break time for me personally. After 2020, new demand will decline, and there is a strong chance that we will fall into a structural recession. Rather than demand new buildings, I think it will be important to look at an attractive way to coordinate the large volume of real estate stock and personnel resources that will remain after the Olympics. Japan is said to have a sophisticated response to challenges. We are probably going to be able to take lessons from meeting challenges and make them available globally. There was a time when I wanted to be jet-setting around the world for my work, but as someone who was born and raised in Japan, I feel attracted to the notion of taking the local knowledge that I can only obtain here in Japan, and delivering it directly to the world. I want to take the knowledge gained from my office research and apply it to an increasingly wide range of fields.